NOVA MCGILL

Contributor

It marked the beginning of a new era, as it was the beginning of what would remain as a communal public act throughout the history of this art form. This revolutionary act took place for the first time in history on December 28, 1895 in Paris, France, in which a set of short films was exhibited collectively in a paid audience for the first time, as a presentation that took place in the Salon Indien du Grand Café, offered by two brothers named Auguste and Louis Lumière. Although there were precedents antecedent to this presentation, it is known in history as the true beginning of cinematography.

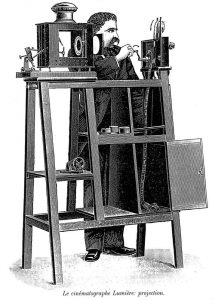

Prior to the screening by the Lumière brothers, motion pictures were essentially novelty experiments, which people could view one at a time using devices like Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope. These devices enabled viewers to observe a short loop of moving pictures only after peering into a box alone. Though they were intriguing, they lacked the symbolic act of communal participation that came with film viewing. With their invention, referred to as the Cinématographe, as their filmmaking tool consisting of the camera, processor, and projector combined, the Lumière brothers started shifting this trend. They were able to display their films on a screen for people to witness. For the first time in history, people observed motion pictures as a social phenomenon rather than as an individual peculiarity.

The evening’s lineup consisted of a series of ten short films, each less than a minute in length. Among the most famous would prove to be “Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory,” where workers walked in front of the camera before leaving a factory at the end of the working day. The other subjects consisted of feeding a baby, a gardener outwitting a child for playing with his water hose, and trains coming into the station. These films had no actors, plots, or special effects; just the ordinary minutiae of everyday life filmed in action. The lack of polish in no way reduced the sense of wonder experienced by their observers. The task of carrying out everyday chores in what was almost but not quite real life and magnifying them to great size onto a screen was at times jolting and even thrilling.

One of the most famous legends about the screening is associated with “Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat.” According to legend, some members of the audience shocked or panicked in response to an oncoming train that seemed about to break through the screen. While historians have disputed the facts of this incident, it seems to capture very well just how “real” moving images appeared to those first viewers. It truly seemed to matter that reality itself was moving and repeating in front of their very eyes.

The success in this commercial venture made the cinema industry start considering the whole of Europe and the rest of the world in a remarkably short span. Film shows began traveling to movie houses, carnivals and cafes, and the act of film viewing turned into a form of entertainment for the masses. Even as the Lumiere brothers believed cinema would lead to nothing but a momentary phenomenon, soon other cinematographers began delving into its storytelling possibilities. In no time, directors such as Georges Melies began incorporating fictional concepts and fantasy worlds into their works, and cinema was no longer about documentation alone. The effects brought about by this first commercial screening of a film far exceeded the duration of the screening itself. It provided a platform for politics, cultures, educations, and identities to be affected by it. Film became a platform for the preservation of history and for ideas to be exchanged, as well as for public opinions to be constructed out of it. The films began to create an industry characterized by cultures that reached dominance status; this was among a few instances that films as a form of art and cultural expression had reached on screens internationally on such a short period and duration as a technological advancement. It can now be said that the event put forward by the Lumière brothers in 1895 is indeed much more and beyond mere technological and scientific advancement because it was at that moment that, “humanity presently revealed a new way to gaze at itself with binoculars pointing inside rather than outwards or upwards at stars or God or at infinite possibility beyond and above and around itself as mere mortal mortals in all their mundane and mundane-inured existences and dimensions within and beyond their particular time-space as such as mortals with all their grandeur or power or intelligence or ingenuity—present and future and even beyond we mortals always are, as we are always possessing as mortals so-in and so-called.”

Photo by Lumière