NOVA MCGILL

Contributor

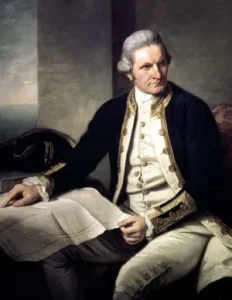

The landing of Captain James Cook in Hawai‘i was more than a marking on a map; it is a profoundly human event that is intertwined with curiosity, hope, and the longing that comes with entering the unknown. On January 18, 1778, during his third voyage across the Pacific Ocean, Cook’s expedition encountered the Hawaiian Islands while searching for the Northwest Passage. The sight of land after the endlessness of the sea, the storms, and the exhausting journey itself brought a wave of relief as well as rejuvenated hope for the expedition members. They could never imagine the impact their landing would create.

Cook’s first landing took place on the islands of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau, where he encountered Hawaiians, whose embracing and welcoming nature made its presence known. These were not people waiting for discovery but already thriving communities—expert farmers, accomplished sailors, and customs that permeated every aspect of life. The Hawaiians were hospitable to the men of Cook’s crew, and the initial interactions with them were characterized by tentativeness and trade. Cook’s decision to name the group of islands the ‘Sandwich Islands’ in respect of his patron expressed the usual trend among Europeans, but the islands’ own authentic history and richness set them apart from others.

When Cook landed back in Hawai‘i in 1779, the dynamic changed. Familiarity led to animosity, and the list of misunderstandings grew. Cultural differences expanded and the competition for resources tested the fledgling relationship. A shared curiosity blossomed into suspicion, until the conflict erupted in Cook’s killing at Kealakekua Bay—a violent and unexpected end that startled both the Cook party and the Hawaiians, proving how quickly first contact can turn disastrous when communication declines.

Cook did not live long enough to witness what led to or resulted from his appearance, but Hawai‘i saw it all. The appearance of Cook brought the islands into contact with a much wider world, and this brought trade, exploration, and foreign activity that would result in changes to Hawaiian society of immense proportions. History is not just about dates and events but about people interacting and making decisions, as well as dealing with those decisions long after the event is over, as this chapter will recount.

Photo from Britannica.com